The Digital Bushmen: UAS for wildlife tracking in Namibia

What happens when you mix ancient Bushmen knowledge with the latest in drone technology? Our experiment of joining these two very opposite worlds presents a completely new way of counting wildlife.

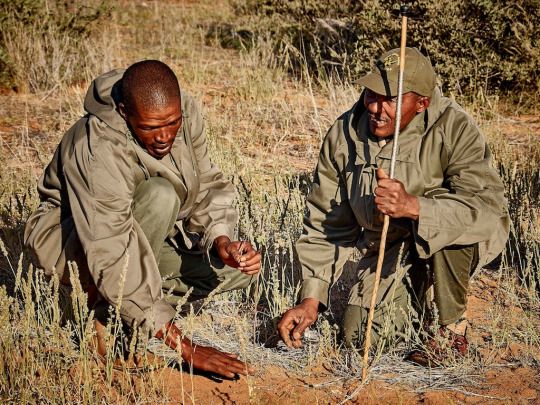

Meeting the San

The San are an ethnic group often regarded as the best wildlife trackers in the world. For millennia, they have lived as hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari desert relying on an intimate knowledge of the environment. For the most part, the Kalahari is a redundant, almost featureless flat and arid landscape covered in thorny bushes. The fact that people were able to develop the tools and skills to navigate and sustain themselves in such harsh conditions is truly remarkable. Unfortunately, despite some conservation efforts, traditional knowledge and bush skills are vanishing among the new San generations. Given the increasing demand to track wildlife for tourism, those who do have the skills usually find a job without too much difficulty and Kuzikus Wildlife Reserve employs a trio of San trackers: Gouse, Watson and John.

A friendly “San vs Drones” competition

Equipped with the latest in drone mapping technology, we imagined that we could rival at least a bit with San knowledge, and were utterly ridiculed by the Kuzikus San. Early one morning, we set up a friendly competition between our technology and the San with the goal to find a newborn black rhino: us with the drones equipped with a thermal camera and the San just with their sandals and knowledge of the area the rhino was suspected to be found. Our drones weren’t even up in the air when Gouse and John already came back and told us the direction and range to the nearest rhino. This technologically humbling experience was a real eye opener, a clear demonstration of how valuable traditional skills are despite new technologies. It was also one of the reasons why we started thinking about finding ways to involve the trackers in our work.

The challenge of counting animals

Having updated counts of how much of various animal species are present in a defined area, like Kuzikus wildlife reserve or parts of a national park, is one of the key numbers used in nature conservation, just like how much rain this area has been receiving and other natural events influencing the land. Counting wildlife remains one of the most challenging tasks in nature conservation and wildlife management. Despite important advances in technology, the most effective methods for game counts still widely used today are a far stretch from technology. The most commonly used technique is called “Transects”, consisting of driving with a car or flying with a small manned aircraft or helicopter in straight lines over a defined area, counting animals on the go. This method asks for very good piloting and counting skills and relies heavily on approximation.

We already tried to address the challenge of game counts using drone technology last year in collaboration with Micromappers (read the blog here), and we learned that non-expert crowdsourcing was a very effective tool to rapidly tag animal locations. But when it comes to accurate animal identification, things become more delicate and as of today even artificial intelligence still requires the help of expert knowledge to be trained.

Bushmen turned digital

With thousands of aerial images in the bag, parts of our Namibia team left back home while Matthew Parkan (of the LASIG lab at EPFL) and Friedrich Reinhard (of Kuzikus Wildlife Reserve) took on the experiment of involving the San trackers in identifying and counting animals in our drone imagery. Matthew and Fritz set the experiment up as an interview with two parts.

The first part consisted of general questions about the San’s personal background and overall familiarity with spatial thinking to evaluate their exposure to aerial perspective and get an insight into their traditional way of dealing with navigation in the bush. We learned that all of them had previously been exposed to maps, however, they themselves never really used them. The main conclusion drawn from the first part of these interviews was that their navigation (and the way they share it) relies on effectively integrating a story arc with landmarks to create a mental map.

The second part included a test of image interpretation to localize and identify animals in a set of aerial images. To start out this second part, we showed Watson, Gouse and John an orthophoto covering the Kuzikus compound and the nearby San village where they live. We were confident that they would recognize the setting immediately, but it turned out that just getting familiar with the computer was already a hindrance. We are so used to deal with computers, it’s easy to forget we had to learn it once. So we went through a crash course in computer handling and provided them with examples of different objects or animals and their shadows in one image. After a few tries, they were able to browse through the images on their own and caught on fast.

Expert analysts

John, Gouse and Watson spotted most of the animals in the various images and provided us with consistent interpretations of the species and sometimes even of the tracks in the high grass. However, what impressed us most was that the San pointed out subtle differences in the shades that would give away the animals’ identities, like for example, teaching us that Blue Gnus have shorter necks than most other animals. They were even able to give us the name of one of the Black Rhinos they spotted! For people who had never seen aerial imagery, their performance was truly remarkable. Undoubtedly, with a bit of additional training, the San trackers could easily become expert image analysts. Yet another illustration that integrating traditional knowledge with modern technology is not only an elegant way of keeping it alive, but potentially also an effective approach to address some of our modern technical and scientific challenges.

About our Namibia mission

Our Namibia mission is part of SAVMAP, a joint initiative between the Laboratory of Geographic Information Systems (LASIG) of EPFL, Kuzikus Wildlife Reserve and Drones For Earth that aims at better integrating geospatial technologies with conservation and wildlife management in the Kalahari. While most of our effort on this mission was invested in mapping various sites of interest with a variety of sensors (RGB, NIR, RE, multispectral and thermal) to analyze growth patterns and influences such as bush fires, cattle farming, wildlife stress on the natural habitat, we also took advantage of trying out completely new ideas on how drone technology can help nature conservation.

Photo credits

Some of the beautiful photos used in this blog have been taken and kindly shared with us by photographer Karin Falk.